The Empire opened as a cinema in 1928. There had been a theatre on this site in Leicester Square since 1884. Originally specialising in ballet and then in variety acts, the theatre became a mainstay of the West End entertainment scene. It was especially popular with young ‘men about town’, although it encountered the anger of the London authorities in the 1890s for the use of sexual innuendo on its stage and the presence of prostitutes soliciting clients in the auditorium.1

A plan to rebuild the Empire Theatre and convert the neighbouring Queen’s Hotel into a cinema was proposed as early as 1919.2 Over the next few years, several entrepreneurs and investors expressed interest in the site, including the Canadian cinema chain Allen Theatres, apparently eager to create an international theatre circuit, who envisioned building two mammoth ‘picture palaces’ side by side.3 None of these plans moved beyond the planning stage, although the theatre was used occasionally during the 1920s for gala presentations of new films. In 1925, the site was acquired by the Metro-Goldwyn Film Corporation of America (later MGM) and the British company Jury-Metro-Goldwyn (the same year the company took direct control of the Tivoli), who began the process of turning the iconic West End music hall into a ‘shop window’ for Hollywood films.4

The new owners employed the New York architect Thomas W. Lamb, who worked with Frank Matcham’s London-based firm, to design a lavish cinema with more than 3,000 seats (plans called for 3,344 but the actual number may have been slightly smaller). This was around twice the capacity of the former variety theatre, and drew extensively on Lamb’s designs for the Albee Theatre in Cincinnati and the Capitol Theatre in New York City.5 Like other large cinemas, the building featured extra amenities such as air conditioning, ‘cosmetic rooms’ for ladies, ‘smoking rooms’ for men, telephone kiosks and a café (the 400-seat Tudor Coffee Room).6 The new Empire’s stated policy was ‘to present the world’s finest pictures amid the most luxurious surroundings at the lowest possible prices’.7 In practice, and in common with other West End cinemas, its prices were higher than the average for cinema tickets, catering to those who were willing to pay a premium to see the newest releases in lavish surroundings.

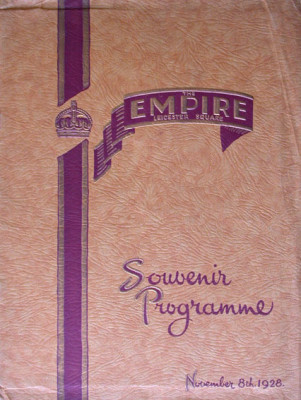

The Empire cinema officially opened on 8 November 1928, with an adaptation of Arthur Wing Pinero’s play about a Victorian theatre company, Trelawney of the Wells. The trade magazine The Bioscope approved of the choice, saying that although the film was produced in Hollywood, with an American star (Norma Shearer), the story was ‘spiritually British’.8 Behind the scenes, however, Vivan Van Damm, who had been appointed by the late Marcus Loew as the cinema’s British manager, recalled a frosty relationship with his American counterpart, David Goldenberg, previously sent over to manage the Tivoli. They disagreed over how the cinema should be run, and Van Damm was soon fired.9

Sound-film apparatus had been installed during the reconstruction of the Empire, and the cinema hosted its first feature-length ‘talkie’, the MGM musical The Broadway Melody in 1929. During the opening week of the film, the Empire sold nearly 83,000 tickets, making it the busiest week in the theatre’s history, and possibly the biggest single week of any West End cinema.10 The Empire continued to show first runs of MGM releases into the 1930s.11 The interior was demolished and rebuilt entirely in 1961. In 2015 it is still open as a cinema as part of the British-based Empire Cinemas chain.12

Image: Souvenir opening programme for the Empire Theatre, 8 November 1928. Credit: Courtesy of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, University of Exeter: www.bdcmuseum.org.uk.

Further reading:

- Allen Eyles with Keith Skone, London’s West End Cinemas, third edition (Swindon: English Heritage, 2014).

- Allen Eyles (ed.), Picture House, 13 (Summer 1989). Special issue, ‘The Empire that Was, 1928-1961’.

- Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchinson, Lost Theatres of London (London: Hart-Davis, 1968).

- Cathy Ross, Twenties London: A City in the Jazz Age (London: Museum of London/Wilson, 2003).

- Vivian Van Damm, Tonight and Every Night (London: Paul, 1952).

- Susan Pennybacker, ‘“It Was Not What She Said But The Way That She Said It”: The London County Council and the Music Halls’, in Peter Bailey (ed.), Music Hall: The Business of Pleasure (Milton Keynes: Open University, 1986), pp. 118-140; Judith Walkowitz, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 44-63. ↩

- ‘New Empire in a New Leicester Square’, The Times, 10 April 1919, p. 10. ↩

- ‘Canadian Exhibitors’ £1,000,000 Enterprise’, The Bioscope, 10 June 1919, p. 19. For Allen Theatres, see Paul Moore, ‘Allen Theatres: North America’s First National Cinema Chain’, Marquee, 40:3 (2009), 4-6. ↩

- ‘Future of the Empire Theatre’, The Times, 26 August 1925, p. 8. ↩

- Allen Eyles with Keith Skone, London’s West End Cinemas, third edition (Swindon: English Heritage, 2014), p. 89. ↩

- ‘The New Empire a Reality’, The Bioscope, 7 November 1928, pp. 35, 38; Empire Theatre souvenir programme, 8 November 1928, Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, University of Exeter, EXEBD 18925. ↩

- Empire Theatre souvenir programme, 8 November 1928. ↩

- ‘The New Empire a Reality’, p. 35. ↩

- Vivian Van Damm, Tonight and Every Night (London: Paul, 1952), pp. 52-4; ‘New Empire in Sept’, Variety, 28 March 1928, p. 4. ↩

- Eyles, London’s West End Cinemas, p. 89. ↩

- John Sedgwick and Clara Partfort-Overduin, ‘Understanding Audience Behaviour through Statistical Evidence: London and Amsterdam in the Mid-1930s’, in Ian Christie (ed.), Audiences: Defining and Researching Screen Entertainment Reception (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, 2012), pp. 96-110. ↩

- ‘About us’, Empire Cinemas Ltd website: http://www.empirecinemas.co.uk/about_us. ↩