Overview

Early cinema

‘Electric theatres’

World War I

The 1920s

The coming of sound

Conclusion

Bibliography

Overview

Film has been part of life in London since 1896, when the first ‘cinematograph’ shows in the country were given to the public. London at that time was the biggest city in the UK by far, with a population of around 5.5 million, five times as large as either Liverpool or Manchester. In the following decades, the cinema emerged as an important new source of entertainment for millions of Londoners, many of whom had few other opportunities for commercial leisure. By 1914, there were around 500 cinemas in London. And, while the number of venues dropped to around 400 in the 1920s, the average size of London’s cinemas increased, with some seating as many as 2,000 or 3,000 patrons.

For many people, cinemas and the films they showed were windows onto a new world. Silent films were international products, and, by the end of World War I, the vast majority of the films shown on British screens came from Hollywood. But, at the same time, cinemas were also part of very local patterns of life. ‘To you or me,’ said Graham Sutton, writing about Londoners’ cinema-going habits in 1926, ‘there are but half a dozen picture-houses: two or three away in the West End, where we go occasionally to see some special “attraction”; and two or three more at our very doors.’1 By the end of the 1920s, when silent films were giving way to ‘talkies’, cinemas had become a ubiquitous presence in London and its expanding suburbs, with some dedicated film fans in the city going to the cinema as many as three or four times a week.2

How did cinemas in London become so central to so many people’s lives? And what evidence do we have to tell us about the experience of cinema-going in London during the silent era? Read on to find out more about the history of London’s cinemas.

Early cinema

The first public film shows in the UK to a paying audience took place in London in 1896. On 21 February that year, the Polytechnic Institute on Regent Street hosted a display of the Lumière brothers’ new moving-picture device, the Cinématographe. Later the same day, the inventor Robert Paul demonstrated his own device, the Theatrograph (later re-named the Animatographe), at the Finsbury Technical College. By the end of the year, the Animatographe was on the bill at the Egyptian Hall on Piccadilly and at the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties in Leicester Square. Meanwhile, the Cinématographe had migrated across to the nearby Empire Theatre, while another rival invention, the American Biograph, was soon to become a regular feature at the Palace Theatre on Cambridge Circus.3 Before long, moving pictures quickly became a special attraction at music halls and variety theatres around the city.

There was no official cinema licensing or censorship system in place in the UK in the early years. But the local authorities in London were keen to guard public safety, as well as to protect their own standards of morality, and so they kept a close eye on venues showing films. A fatal fire at a film screening in Paris in 1897 made local officials especially wary. The following year, the London County Council (LCC), the local government body for inner London, introduced their first set of regulations concerning film shows.4 The LCC’s records over the next decades suggest the variety of places in which moving pictures were exhibited. For instance, when the LCC conducted a survey in 1908, they found that films were not only being shown regularly in variety theatres, but also in a number of churches, chapels, mission halls, Salvation Army hostels, workhouses, public halls, schools, shops and fairgrounds.5

The people who exhibited early films in London were equally varied. There were individual showmen, like the magician David Devant, who toured from venue to venue, as well as companies who hired out projectionists and film lecturers for special screenings.6 Travelling ‘bioscope’ shows, which toured the national fair circuit, were also frequent visitors to London, and continued to visit until the early years of World War I.

‘Electric theatres’

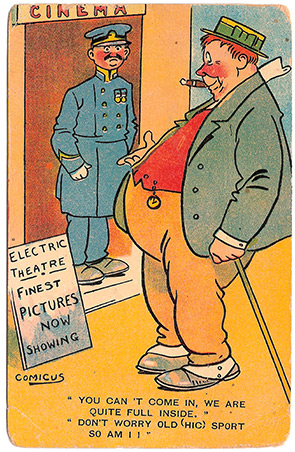

Throughout the early period, there were attempts to open full-time moving-picture shows in London. But the idea of a permanent venue for showing films only gathered steam around 1906, when several cinemas, or ‘electric theatres’, opened. One of the first was the Daily Bioscope at 27-28 Bishopsgate in the City of London. This initially opened in a converted ground-floor residence as a relatively upmarket venue catering to local office workers, and specialising in films of current events. But it was soon sold to new managers, who switched to more populist fare.7 Other early permanent cinemas included Gale’s Bioscope Show in Stratford, which opened in a converted sweet factory, and the Carlton Theatre in Greenwich, a former variety venue, later re-named the Cinema de Luxe.

Like the ‘nickelodeons’ that appeared in America around the same time, some of London’s early cinemas, including the Daily Bioscope, were extremely cheap, charging prices of one or two pence, and catering to the city’s poorest pleasure-seekers. Because of this, and also because cinemas were becoming especially popular with children, the LCC and the Metropolitan Police continued to monitor cinemas in London closely.8 Local police reports provide fascinating glimpses of what early cinemas in London were like, even if the police’s views tended to be those of non-cinema-goers, who were often deeply suspicious of this new form of entertainment. For instance, when the Superintendent at the Southwark Station police branch visited the Bio-Picture Land Theatre on Trinity Street, Borough, in March 1909, he thought that the crowded conditions, where boys and girls sat together, were ‘very demoralising’, and that ‘the place lends itself to indecent practices’.9 In contrast, children growing up in London during this time tended to remember the crowded nature of many cinemas as adding to the excitement and fun of the moving-picture show.10

Many early cinemas in London were converted from existing buildings, such as shops or skating rinks (roller-skating having been a popular pastime in the 1900s). But other venues were built specially for the purpose of showing films. From 1909, the Cinematograph Act, which regulated film exhibition at a national level, contributed to a ‘boom’ in cinema-building in London. Evidence from the LCC’s licensing reports and early film trade directories suggest that the total number of cinemas in and around London increased from 133 in 1909 to 349 in 1911. By the end of 1914, there were as many as 522 cinemas in London and its suburbs.11 These included several local cinema circuits, including Electric Theatres (1908) Ltd, which controlled 16 cinemas in the London area by 1910.12

While some of these early cinemas seated fewer than 100 people, London also boasted some of the biggest and most lavish ‘picture palaces’ in Europe, if not the world. An American tourist on holiday in London during the summer of 1914, who visited a cinema in the Strand, noted in her diary that London’s West End cinemas were ‘as pretentious as our best theatres’.13

World War I

After Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914, London became increasingly caught up in the war effort. This was reflected in the content of the films shown in London, as well as the atmosphere inside its cinemas. For instance, in November 1914, the ‘thrilling war drama’ Warfare in the Sky was on the top of the bill at the Clapton Cinematograph Theatre in Hackney. Meanwhile, audiences at the nearby Clapton Rink Cinema could study the battle lines on a customised political map of Europe, which also displayed the cinema’s opening times and prices of admission.14 Typically, cinemas in London had to apply for a special music licence if they wanted to provide anything more than a basic musical accompaniment to their films. But, during the war, a number of unlicensed venues were granted permission from the LCC to host patriotic sing-alongs between films in order to help raise public morale.

Not everyone appreciated the atmosphere inside London’s cinemas, though. During World War I, earlier fears about the conduct of the city’s audiences grew worse. Moral and religious reformers, like Frederick Charrington, who had been vocal in the campaign to ‘clean up’ London’s music halls in the 1890s, produced evidence of indecency inside London’s cinemas. This included accusations of male and female prostitution and child prostitution. Subsequent investigations organised by the Metropolitan Police were less damning. But they did suggest that cinema staff were habitually turning a blind eye to sexual behaviour between adults (including between women and soldiers) going on in the darkness of the auditorium.15 Such fears may have been a product of the larger climate of moral panic that gripped London at various points during the war years. But the LCC and neighbouring councils took the complaints seriously enough to tighten up their regulations, and, in the case of one cinema in Finsbury Park, to prosecute the proprietor for disorderly conduct.16 Elsewhere, the death of four children in a stampede at the Electric Theatre Picture Palace in Deptford added to ongoing calls for proper supervision of children inside London’s cinemas.17

Anyone trying to keep track of cinema audiences in London certainly had their hands full. Across Britain, weekly levels of cinema attendance soared during the war, reaching an estimated 18 million at the start of 1916 and 21 million in 1917.18 This rise can be attributed partly to the increased marketing of film stars, such as Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin, and to the success of film serials and longer feature films. But it was also partly a result of the popular appeal of newsreels and official war films like The Battle of the Somme, released in 1916. The Battle of the Ancre, otherwise known as the ‘Tank’ film, was also hugely popular when it was released the following year. One film trade journalist reported that it was being shown at 112 cinemas in London in a single week, and that ‘long queues, “house full” boards and advance bookings were the order of the day’.19

Despite the overall rise in cinema-going in Britain, the war had a negative impact on a great many of London’s cinemas. National conscription into the armed forces, introduced in January 1916, and soon extended to all men aged 18-50, took away a large proportion of cinema staff. Women were able to take over the management in some cinemas, and, in a few cases, like the Pleasureland cinema in Brixton, women took over projection duties, too.20 However, some cinemas were forced to close. In addition, the Entertainments Tax, which came into force in May 1916, imposed an extra charge on cinema tickets that may have hit smaller venues particularly hard. The ban on luxury buildings also meant that only a handful of new cinemas opened during the war. In all, the number of cinemas in the London area dropped from around 522 in 1914 to 409 by the time the Armistice was signed in 1918.

The 1920s

After the war, the film industry in Britain anticipated a high demand for more cinemas. From 1919, as wartime building restrictions were lifted, construction work began on large ‘super cinemas’ around the country.21 In London, this trend was visible in new venues like the Palmadium cinema in Palmer’s Green, which opened in 1920, or the Premier Super Cinema in East Ham, completed in 1921, each of which had more than 2,000 seats. It’s worth noting that the demand for more and bigger cinemas wasn’t felt everywhere in London to the same extent. In 1919, a cinema construction project in Brick Lane sparked a small riot, when local residents objected to being thrown out of their houses to make way for yet another ‘picture palace’.22 But, in general, the average size of cinemas in London increased during the 1920s. According to the New Survey of London Life and Labour, the total number of cinema seats in inner London reached 268,000 in 1929, equivalent to one cinema seat for every 20 people. This was more than twice the number of theatre and music hall seats combined.23

Inside London’s cinemas, the experience of watching films and the styles of showmanship remained very varied. Some cinemas established a reputation for using live performers, music and scenery to create elaborate ‘prologues’ for new feature film releases.24 At the Shepherd’s Bush Pavilion, where Leonard Castleton Knight was in charge of gala ‘presentations’, audiences in 1925 were treated to a theatrical encounter between an Egyptian slave master and his slaves, illuminated with special lighting effects, to introduce screenings of the Hollywood fantasy film The Thief of Bagdad.25 Other London cinemas specialised in combining live acts and films in a format known as ‘cine-variety’. For instance, the Plaza on Lower Regent Street, which opened in 1926, employed its own Tiller Girls dance troupe to perform as part of the programme.26 But, while such exhibition practices were popular, the majority of cinemas in London were not able to accommodate large stage shows. In fact, many of the first generation of pre-World War I cinemas remained open throughout the 1920s, including cinemas that had been built as early as 1909. Surviving programmes and newspaper listings from the period suggest that a trip to ‘the pictures’ for most Londoners usually consisted of a main feature, a newsreel and a selection of short films, all with musical accompaniment.

By the end of the 1920s, the British film industry, including film exhibition, had become big business. A growing number of London’s cinemas were controlled by national circuits, like Associated British Pictures (ABC) or the Gaumont-British Picture Corporation.27 A few cinemas in the West End were controlled by Hollywood companies, including the Empire in Leicester Square (re-built from the former variety theatre), which was opened in 1928 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a ‘shop window’ for the company’s new releases.28 At the same time, some exhibitors and film enthusiasts in London attempted to promote the notion of film as a modern art form by creating more refined film-viewing environments. The Film Society, a membership club for showing uncensored and un-commercial films, was established in London in 1925.29 And, in 1928, the Avenue Pavilion on Shaftesbury Avenue became one of the city’s first dedicated ‘art’ cinemas, a policy that lasted until the end of the decade.30

The coming of sound

There had been experiments in synchronising recorded sound to moving images since the end of the nineteenth century. But sound films only became widespread internationally in the late 1920s. The first feature-length film with synchronised singing and dialogue, the Warner Brothers musical The Jazz Singer, premiered in London at the Piccadilly Theatre on 27 September 1928, a year after its American debut.31 More feature-length ‘talkies’ were released over the following months, building up an audience for the new novelty. George Thomas, who lived in a tenement flat overlooking Berwick Market in Soho, experienced his first sound film in May 1929, when he went to see (and hear) the film musical Broadway Melody, probably at the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square. ‘From now on,’ he wrote in his diary, ‘I am an ardent “talkie-fan”, in the sense that I will never refuse a chance of going again.’32

Silent films and sound films co-existed for several more years. In fact, some cinemas in Britain were still showing silent films in 1933.33 In London, as elsewhere in the country, the conversion of cinemas to sound technology was a gradual process. By 1930, according to the information given in the annual Kinematograph Year Book, only around 150 of London’s 400 or so cinemas had been ‘wired’ for sound.34

Conclusion

Writing in 1922, E.V. Lucas thought that cinemas, like motor cars, tube trains and other modern inventions, had done their best to change the character of London. But, he said, ‘they are not strong enough. London merely adds them to her system and remains London still.’35 As this brief guide to London’s early cinema history suggests, cinemas clearly did have a big impact on the life of the city. They provided entertainment for millions of Londoners, and altered the face of hundreds of streets. But cinemas also operated within London’s existing ‘system’. They responded to local tastes and changed as the city changed. The more we find out about local exhibition across London and its suburbs, the more we can understand exactly how much, and in what ways, cinema has contributed to the city’s history.

Further reading

You can find suggestions for further reading about London’s early cinema history on the Bibliography page.

- Graham Sutton, ‘The Coming of the Cinema’, in St. John Adcock (ed.), Wonderful London, 3 vols (London: Fleetway Press, 1926), vol. 3: p. 1077. ↩

- Angus MacPhail, ‘Testing the Public Pulse’, Kinematograph Weekly, 11 August 1927, p. 37. ↩

- John Barnes, The Beginnings of the Cinema in England (Newton Abbott: David and Charles, 1976). ↩

- Tony Fletcher, ‘The London County Council and the Cinematograph, 1896-1900’, Living Pictures: The Journal of the Popular and Projected Image Before 1914, 1:2 (2001), 69-83. ↩

- Nicholas Hiley, ‘“Nothing More than a ‘Craze’”: Cinema Building in Britain from 1909 to 1914’, in Andrew Higson (ed.), Young and Innocent? The Cinema in Britain, 1896-1930 (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2002), pp. 111-27. ↩

- Tony Fletcher, ‘A Tapestry of Celluloid, 1900-1906’, Early Popular Visual Culture, 4:2 (2006), 175-221. ↩

- Jon Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures: Film Exhibition in London during the Nickelodeon Era, 1906-1914’, Film History, 16:1 (2004): 78. ↩

- Jon Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures II: Indecency, Anarchy and Junk Film in London’s “Nickelodeons”’, Film History, 16:2 (2004), 172-97. ↩

- Report by the Superintendent of the Southwark Station branch, ‘M’ Division, Metropolitan Police, dated 23 March 1909, National Archives, MEPO 2/9172, File 590446/5, ‘Bioscope and Cinematograph Shows’. ↩

- Luke McKernan, ‘“Only the Screen Was Silent…”: Memories of Children’s Cinema-going in London before the First World War’, Film Studies, 10 (2007), 1-20. ↩

- To find out more about the sources for this data, see the ‘Sources’ section on the London’s Silent Cinemas Map. ↩

- Luke McKernan, ‘Unequal Pleasures: Electric Theatres (1908) Ltd. and the Early Film Exhibition Business in London’, paper given at the Emergence of the Film Industry in Britain conference, University of Reading Business School (2006), available on author’s website <http://lukemckernan.com/wp-content/uploads/unequal_pleasures.pdf>. ↩

- Dora Leba Lourie, ‘My Trip Abroad’ (1914), unpublished travel diary, University of Westminster Archive, ACC1999/5. ↩

- Programme for the Clapton Cinematograph Theatre, week beginning 23 November 1914, and poster for the Clapton Rink Cinema, c.1915, Hackney Archives, items M4630 and BK/17–791, Y14825. ↩

- Paul Moody, ‘“Improper Practices” in Great War British Cinemas’, in Michael Hammond and Michael Williams (eds), British Silent Cinema and the Great War (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 49-63. ↩

- Alex Rock, ‘The “Khaki Fever” Moral Panic: Women’s Patrols and the Policing of Cinemas in London, 1913-19’, Early Popular Visual Culture, 12:1 (2014), 57-72. ↩

- Report to the LCC Theatre and Music Halls Committee, presented papers, meeting of 2 May 1917, London Metropolitan Archives, LCC/MIN/10,996, item 4. ↩

- Nicholas Hiley, ‘The British Cinema Auditorium’, in Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (eds), Film and the First World War (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995), pp. 160-70. ↩

- ‘Weekly Notes’, Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly, 18 January 1917: p. 1. ↩

- Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 15 March 1916, London Metropolitan Archives, LCC/MIN/10,737, item 33. ↩

- Richard Gray, Cinemas in Britain: One Hundred Years of Cinema Architecture (London: Lund Humphries/Cinema Theatre Association, 1996). ↩

- ‘A Housing Scandal from Brick Lane’, East London Observer, 30 August 1919, p. 2. ↩

- H. Llewellyn Smith (ed.), New Survey of London Life and Labour: Volume I: Forty Years of Change (London: King, 1930), p. 291. ↩

- Julie Brown, ‘Framing the Atmospheric Film Prologue in Britain, 1919-1926’, in Julie Brown and Annette Davison (eds), The Sounds of the Silents in Britain (Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2013), pp. 200-21. ↩

- ‘Selling the Picture to the Public’, Bioscope, 19 February 1925: p. 75. ↩

- Allen Eyles, London’s West End Cinemas, third edition (Swindon: English Heritage, 2014), pp. 74-7. ↩

- Robert Murphy, ‘Fantasy Worlds: British Cinema between the Wars’, Screen, 26:1 (1985), 10-20. ↩

- Vivian Van Damm, Tonight and Every Night (London: Paul, 1952), pp. 52-4. Van Damm was one of the original managers of the Empire cinema. ↩

- Jen Samson, ‘The Film Society, 1925-1939’, in Charles Barr (ed.), All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British Cinema (London: British Film Institute, 1986), pp. 306-13. ↩

- To find out more about London’s early art cinemas, see the ‘Cinema and the West End’ exhibition on this website. ↩

- Rachael Low, The History of the British Film, 1918-1929 (London: Allen and Unwin, 1971), p. 203. ↩

- George Thomas, A Tenement in Soho; Or, Two Flights Up (London: Cape, 1931), p. 213. ↩

- Robert Murphy, ‘The Coming of Sound to the Cinema in Britain’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 4:2 (1984): 151. ↩

- The Kinematograph Year Book for 1930 (London: Kinematograph Weekly, 1930). ↩

- E.V. Lucas, ‘The Charm of London’, in Burrow’s Guide to London (London: Burrow, 1922): p. 6. ↩