The Electric Cinema Theatre at 6 Ingestre Place, also known as the Jardin de Paris, was open for business by October 1908.1 Ingestre Place is a short street in the heart of Soho near Golden Square. In 1908, it was bookended by a brewery to the north and a council board school (the ‘Pulteney’) to the south. Compared to other parts of Soho, the street was considered to be ‘English’ in character.2 But the ethnicities and backgrounds of its residents were still characteristically varied. Next to the cinema at 7 Ingestre Place, according to the 1911 census returns, lived families with roots in Sweden, Germany, England and Ireland, working as tailors, brewers, printers and kitchen workers. The owner of the cinema, Mons. Felix Haté, was French by birth, although he lived outside of Soho in Earls Court. Haté was a chemist, who had developed a chemical process for extending the life of films that had become ‘oily, dirty’ and ‘disreputable-looking’ for the benefit of cinema exhibitors dealing in second-hand or scrap films.3 Jean Austin, who grew up in nearby Silver Place, remembered that Haté would show the films he was currently ‘cleaning’, operating a system of green, red and yellow lights outside the cinema to indicate which film was playing.4 Haté’s workshop was above the cinema, and the building was also home (in 1911) to the Kearey family – Amy, her four sons, and her husband Henry, who worked as the cinema ‘porter’, or custodian.

The cinema itself was converted from a ground-floor residence and an adjoining stable, which backed onto a narrow carter’s yard called William and Mary Yard. The dancer and film star Jessie Matthews, who lived in William and Mary Yard as a child, wrote that the stables and sheds there were used to store stalls and vans from nearby Berwick Market overnight, and housed the horses used by local tradesmen to transport their stock from Covent Garden each morning.5 Jean Austin also recalled them being used for performing animals – including elephants – from Hengler’s Circus, an entertainment venue on Argyll Street, later replaced by the London Palladium.6 Leslie Wood, in his 1937 book The Romance of the Movies, claimed that the cinema opened with ‘no floor, other than the original cobbles, and the screen was erected over the manger, some of the horse stalls still being there’.7 This may have an exaggeration, but only slightly. In 1910, when an inspector from the London County Council (LCC) visited the cinema, he found part of the auditorium to be ‘a stable yard which has been roughly roofed in with boarding’. There were more boards on the floor, and the seating consisted of plain wooden benches, with space for about 180 people, plus standing room for 40 more. The projection box, situated above the entrance from Ingestre Place, was constructed out of wood and sheet metal. ‘Altogether,’ wrote the inspector, ‘the interior is somewhat crude.’8

From the report of a fire in the cinema at the end of 1908, we know that the musical accompaniment to the films was provided by an automatic piano.9 Police surveys of early London cinemas give us more information about what shows in the Electric Cinema Theatre were like. In March 1909, shows cost 2 pence for adults and 1 penny for children, far cheaper than cinemas elsewhere in the West End. Shows ran from early evening to 11 at night.10 In November 1909, police inspectors were asked to name the ‘best’ and ‘worst’ cinemas in their districts. Local police named the Electric Cinema Theatre as the ‘worst’.11 There had been no complaints about crime or disruption in the cinema, although other reports suggested that local residents were sometimes irritated by children from the cinema playing outside in the street, and one neighbour complained to the council that the venue stayed open as late as 1am during the week.12 But it’s clear that, to an outsider, a converted stables in Soho compared unfavourably to cinemas in more affluent parts of the West End. The police inspector in 1909 described the location as ‘a very thickly populated and overcrowded neighbourhood, amongst poor tenement dwellings’. In contrast to the middle-class shoppers who were found to frequent a nearby cinema on Oxford Street (the Casino de Paris), the Ingestre Place venue was ‘Frequented by poor class Jewish, French and English youths, girls and some adults’.13

When Haté launched his cinema and film cleaning business as a company in 1912, he continued to emphasise the cinema’s appeal to local residents in the ‘Cosmopolitan quarter’ of Soho. He kept prices low (1 or 2 pence for an hour-long programme) in order, he said, ‘to meet the needs of the immediate neighbourhood’.14 But he also had more ambitious plans. In the summer of 1910, the cinema was doubling as the London Cinematograph College and Situations Bureau, a training school and employment agency for cinema projectionists.15 By the start of 1912, Haté was running a second cinema in Fulham, the Munster Electric Theatre at 280 Munster Road.16 There were also plans to expand the Ingestre Place cinema, partly necessitated by the new licensing regulations that came into force in 1910. The cinema was closed intermittently for refurbishment from October 1912, and reopened in January 1913, newly licensed as the Jardin de Paris.17 The floor above was still being used for Haté’s chemical works in November 1913, despite warnings from the LCC to close it or relocate it away from the cinema for safety reasons.18

The cinema lasted several more years into the start of World War I. But Haté’s company was losing money and it was finally wound up in May 1915. When a member of the London Women’s Patrol Committee visited Ingestre Place in June 1916 as part of another survey of London’s cinemas, she found the cinema closed and was told that the business was ‘broke’ by someone ‘who thought [she] wanted to take the empty premises’.19 In September 1916, a plan to reopen the space as the Cinema de Paris was submitted to the council by David Long and Robert Van Steenbergen, who gave their nationalities as Italian and Belgian, living outside of Soho. But they withdrew their application shortly after on the grounds that the project would be too expensive.20 A local resident of Soho later recalled his father using the venue as a Yiddish theatre, the first of its kind in London outside the East End.21 This may have been accurate. In 1917, Samuel Wenter, a ‘naturalised British subject of Russian origin’, applied to use the old cinema for concerts in aid of a Jewish benevolent society and for Talmud Torah classes.22 But, when an LCC inspector found theatrical scenery on the site, the council declared it unsuitable for entertainments, and refused Wenter’s application.23 In the 1920s, the building was demolished to make way for the Lex Garage, now the Brewer Street Car Park.24

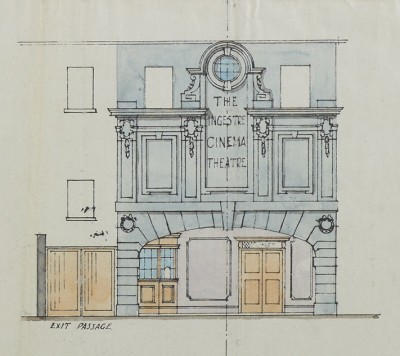

Image: Detail from A.S.R. Ley’s plan of proposed alterations to the cinema at 6 Ingestre Place, 1912. The actual frontage may have been simpler than this. Credit: Courtesy of the London Metropolitan Archives, GLC/AR/BR/19/659.

Further reading:

- Gerry Black, Living Up West: Jewish Life in London’s West End (London: London Museum of Jewish Life, 1994).

- Jon Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures: Film Exhibition in London during the Nickelodeon Era, 1906-1914’, Film History, 16:1 (2004), 60-91.

- Jon Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures II: Indecency, Anarchy and Junk Film in London’s “Nickelodeons”’, Film History, 16:2 (2004), 172-97.

- Allen Eyles with Keith Skone, London’s West End Cinemas, third edition (Swindon: English Heritage, 2014).

- Chris O’Rourke, ‘The Worst Cinema in Soho: Felix Haté’s Side Street Venture’, Picture House, 40 (2015), 13-16.

- Michel Rappaport, ‘The London French from the Belle Epoque to the End of the Inter-war Period (1880-1939)’, in Debra Kelly and Martyn Corrick (ends), A History of the French in London: Liberty, Equality, Opportunity (London: Institute of Historical Research, 2013), pp. 241-79.

- Judith Summers, Soho: A History of London’s Most Colourful Neighbourhood (London: Bloomsbury, 1989).

- Memo from the Sub-Divisional Inspector of the Great Marlborough Street Police Station (‘C’ Division) dated 3 January 1910, London County Council (LCC) Architect’s Department Correspondence Files for 6 Ingestre Place, London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), GLC/AR/BR/07/659. ↩

- Judith Summers, Soho: A History of London’s Most Colourful Neighbourhood (London: Bloomsbury, 1989), p. 163. ↩

- Jon Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures II: Indecency, Anarchy and Junk Film in London’s “Nickelodeons”’, Film History, 16:2 (2004): 180 ↩

- Interview with Jean Austin, 17 May 1994, Oral History Collection, Jewish Museum London, Tape 378. ↩

- Jessie Matthews, Over My Shoulder: An Autobiography (London: Allen , 1974), p. 17. ↩

- Interview with Jean Austin. ↩

- Leslie Wood, The Romance of the Movies (London: Heinemann, 1937), p. 72. ↩

- Memo from Chief Officer, Fire Brigade, to LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee dated 3 January 1910, LMA, GLC/AR/BR/07/0659. ↩

- Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 11 November 1908, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,729, Item 14, p. 523. ↩

- Memo from the Superintendent of the Vine Street Police Station (‘C’ Division) to the Chief of the Metropolitan Police dated 23 March 1909, The National Archives (TNA), MEPO 2/9172, File 590446/5, ‘Bioscope and Cinematograph Shows’. ↩

- Memo from the Superintendent of the Vine Street Police Station (‘C’ Division) to the Chief of the Metropolitan Police dated 2 November 1909, TNA, MEPO 2/9172, File 590446/7, ‘Cinematograph Shows’. ↩

- Memo from Sub-Divisional Inspector E. Anderson, Great Marlborough Street Police Station (‘C’ Division), to London County Council (LCC) dated 3 January 1910, London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), GLC/AR/BR/07/0659; Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 24 July 1912, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,733, Item 119, p. 821. ↩

- Memo from the Superintendent of the Vine Street Police Station (‘C’ Division) to the Chief of the Metropolitan Police dated 2 November 1909, TNA, MEPO 2/9172, File 590446/7, ‘Cinematograph Shows’. ↩

- Company prospectus, July 1912, TNA, BT 31/20750, ‘Haté’s Cinema and Film Cleaning Company, Limited’. ↩

- Advertisement reprinted in Colin Harding and Simon Popple (eds), In the Kingdom of Shadows: A Companion to Early Cinema (London: Cygnus Arts, 1996), pp. 213-15. ↩

- Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 31 January 1912, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,733, Item 264, p. 147. ↩

- Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 4 December 1912, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,733, Item 26, p. 1288. ↩

- Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 3 December 1913, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,734, Item 310, p. 1437. ↩

- Miss Gray, specimen report of the London Women’s Patrol Committee dated 21 June 1916, TNA, MEPO 2/1691, File 976726, ‘Indecency in Cinemas’. ↩

- Application for cinematograph licence dated 21 September 1916, and letter from David Long and Robert Van Steenbergen dated 13 November 1916, presented papers of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls, meeting of 15 November 1916, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,994, Item 23. ↩

- Gerry Black, Living Up West: Jewish Life in London’s West End (London: London Museum of Jewish Life, 1994), p. 49. ↩

- Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 7 March 1917, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,739, Item 22, p. 77. ↩

- Memo from the Chief Office of the LCC Fire Brigade dated 7 February 1917, Architect’s Department Correspondence Files for 6 Ingestre Place, LMA, GLC/AR/BR/07/659; Minutes of the LCC Theatres and Music Halls Committee, meeting of 7 March 1917, LMA, LCC/MIN/10,738, Item 22, p. 77. ↩

- ‘Brewer Street and Great Pulteney Street Area’, in F.H.W. Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: Volumes 31 and 32, St James Westminster, Part 2 (London: London County Council, 1963), pp. 116-37: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp116-137. ↩